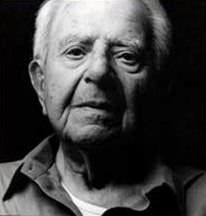

Arpiar Missakian

Arpiar Missakian Born in 1894 in Kessab

In 1909, during the Adana massacres, Turkish soldiers attacked Kessab. I was merely a boy then. They came early in the morning. They were 20,000 strong with Mausers and other artillery. The men of our town fought back, my father among them. But all they had were these ancient hunting rifles. Shifteh, they called them. Not very effective. They lost 50 to 60 men before we fled. They held off the Turkish army until noon or so, then we fled.

With the help of the French, we fled to Latakia to the north on boats. We returned five to six days later to find all our houses burned to the ground. Only charred stone walls remained; everything else was burned. It took us months to rebuild.

In 1915, we were the last to be deported out of Kessab because we were Protestant. The American ambassador in Bolis had apparently secured guarantees for our safety, but we were deported anyway. They took us toward Dier-ez-Zor--the interior Syrian desert. Our whole family: my father, mother, four brothers, two sisters. I was 20 or 21 at the time. We loaded everything we had on mules and horses and set out under armed guards. They took us to Meskene on the Euphrates River. Meskene was a huge outdoor camp where tens of thousands of Armenians had been deported--bit by bit they were sent to Dier-ez-Zor, to their death. We were there for a while. We lived under tents along with a lot of others from Kessab. Most of the time we had nothing to eat. Sometimes my father would buy bread from the soldiers, but they had mixed sand with the flour--so we ate this hard bread, and sand crunched under our teeth.

Meskene was a horrible, horrible place. Sixty thousand Armenians had been buried under the sand there. When a sandstorm hit, it would blow away a lot of the sand and uncover those remains. Bones, bones, bones were everywhere then. Wherever you looked, wherever you walked.

In 1909, during the Adana massacres, Turkish soldiers attacked Kessab. I was merely a boy then. They came early in the morning. They were 20,000 strong with Mausers and other artillery. The men of our town fought back, my father among them. But all they had were these ancient hunting rifles. Shifteh, they called them. Not very effective. They lost 50 to 60 men before we fled. They held off the Turkish army until noon or so, then we fled.

With the help of the French, we fled to Latakia to the north on boats. We returned five to six days later to find all our houses burned to the ground. Only charred stone walls remained; everything else was burned. It took us months to rebuild.

In 1915, we were the last to be deported out of Kessab because we were Protestant. The American ambassador in Bolis had apparently secured guarantees for our safety, but we were deported anyway. They took us toward Dier-ez-Zor--the interior Syrian desert. Our whole family: my father, mother, four brothers, two sisters. I was 20 or 21 at the time. We loaded everything we had on mules and horses and set out under armed guards. They took us to Meskene on the Euphrates River. Meskene was a huge outdoor camp where tens of thousands of Armenians had been deported--bit by bit they were sent to Dier-ez-Zor, to their death. We were there for a while. We lived under tents along with a lot of others from Kessab. Most of the time we had nothing to eat. Sometimes my father would buy bread from the soldiers, but they had mixed sand with the flour--so we ate this hard bread, and sand crunched under our teeth.

Meskene was a horrible, horrible place. Sixty thousand Armenians had been buried under the sand there. When a sandstorm hit, it would blow away a lot of the sand and uncover those remains. Bones, bones, bones were everywhere then. Wherever you looked, wherever you walked.