Dr. Floyd Smith

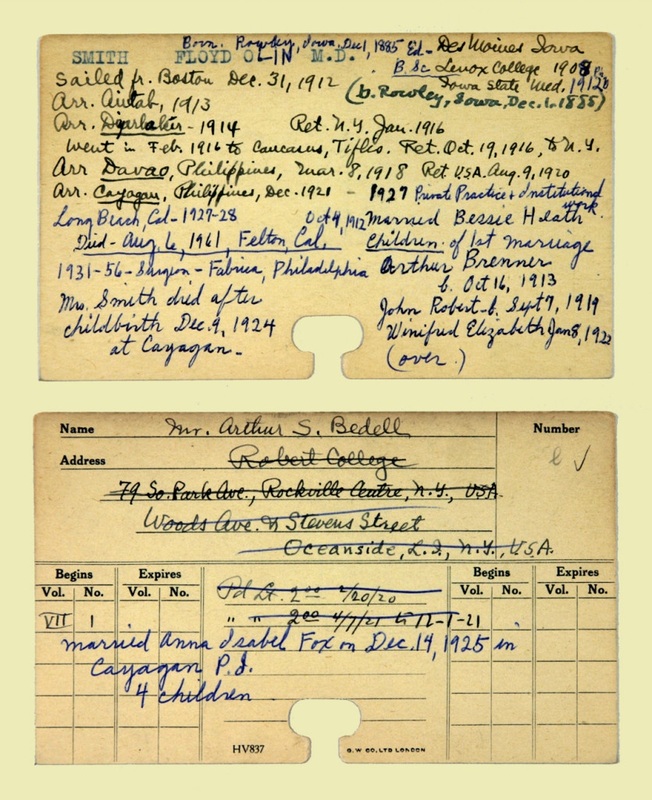

Born on Dec. 1, 1885 in the small farming town of Rowley, Iowa, the fascinating life of Dr. Floyd Olin Smith had a most humble beginning. In the twilight of his life, he wrote, “my parents, Arthur and Jane Smith, were of pioneer stock, who had migrated from ‘back East’ New England, New York, and Ohio.” Wishing their son to have an education, Dr. Smith received his M.D. in 1911 from the University of Iowa following his graduation from Lenox College.

Born on Dec. 1, 1885 in the small farming town of Rowley, Iowa, the fascinating life of Dr. Floyd Olin Smith had a most humble beginning. In the twilight of his life, he wrote, “my parents, Arthur and Jane Smith, were of pioneer stock, who had migrated from ‘back East’ New England, New York, and Ohio.” Wishing their son to have an education, Dr. Smith received his M.D. in 1911 from the University of Iowa following his graduation from Lenox College.

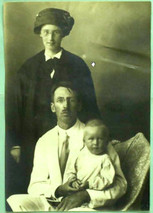

Smith married his college sweetheart, Bessie Mae Heath, in 1912 and they immediately set out for Turkey to begin life as missionaries under the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). The initial passport application indicated they expected to be abroad for eight years. Looking back, Dr. Smith wrote:

If you have a liking for a country of undeveloped resources, something of a wild life at times, where the saddle horse is still the prize means of locomotion, when heterogeneous races are mixed yet separate, where Mohammedan mosques are the dominant architecture, where the entering wedges of Christianity are just finding the grain, a land where patience, wisdom, courage, diplomacy, charm of personality have full play, then apply to the American Board for a post in Eastern Turkey.

What follows is an account of the Smiths’ experience as told through letters, diplomatic correspondence, and personal memoirs.

If you have a liking for a country of undeveloped resources, something of a wild life at times, where the saddle horse is still the prize means of locomotion, when heterogeneous races are mixed yet separate, where Mohammedan mosques are the dominant architecture, where the entering wedges of Christianity are just finding the grain, a land where patience, wisdom, courage, diplomacy, charm of personality have full play, then apply to the American Board for a post in Eastern Turkey.

What follows is an account of the Smiths’ experience as told through letters, diplomatic correspondence, and personal memoirs.

Aintab

Dr. Smith and his wife spent the first six months abroad in Paris learning French and making final preparations for missionary life. After initially stopping at the Bible House in Constantinople, where Dr. Smith passed an exam that allowed him to practice medicine, and attending a missionary conference in Jerusalem, they traveled to Aintab with Dr. Henry Atkinson, who was headed back to Kharpert from the conference.

The first six months in Aintab definitely required an adjustment for the Smiths. In October 1913, their first child, Arthur, was born. The birth was a difficult one for Bessie as she developed several post-partum hemorrhages. In addition, Dr. Smith felt certain that deficiencies existed in his training due to a truncated internship. In Aintab, he was learning from Dr. Fred Shepard, a 30-year veteran missionary. Yet, he felt the large staff already in place in Aintab limited his exposure to work crucial to his development. He offered that it might be beneficial to spend time in Talas while one of the physicians there was on leave to America, a view shared by Dr. Shepard. Dr. Smith had been destined for Diyarbakir from the beginning and, at the very least, felt a nurse would be a necessity there.

In early 1914, Dr. Smith had appendicitis that required emergency surgery. With his illness and Bessie’s long recovery from giving birth, the primary objective of learning Turkish was prolonged. Letters home tell of missionary life at the station and descriptions by proud parents of the growth of their son Arthur. They also warn their parents “not to print anything about the people here which we may send you, for there are Turkish correspondents in America who read the papers and everything about Turkey is sent right back here to the Sultan.”

After about a year in Aintab, the Smiths traveled to Kharpert, passing through Urfa and Diyarbakir where they were able to see their future quarters. They spent the summer of 1914 in Kharpert, where around 50 missionaries and their families attended the annual conference.

In early August, letters home contained the first mention of the anticipated war. Soon, the government began enlisting men between the ages of 20-45. Dr. Smith wrote, “This has caused great anxiety locally, especially among the Armenians. Also the Turks are not at all pleased.” Dr. Smith was able to buy a thoroughbred Arabian horse for 65-75 percent of the true value because the owner feared the horse would be requisitioned by the army.

Interestingly, around this time it seems that many of the Smiths’ letters home never arrived. This caused their families some anxiety and led to inquiries at the State Department.

Diyarbakir

They were unable to leave for Diyarbakir until the end of October 1914. Once in Diyarbakir, correspondence could no longer be done in English, as the government required either Turkish or French be used. Regardless, due to the conditions, there was little correspondence from the Smiths during their time in Diyarbakir.

After the official outbreak of the war, the British consul in Diyarbakir left the papers of the consulate with the Smiths. The intention was to transfer the archives to the American consulate in Kharpert when circumstances would allow. However, when nurse Margaret Campbell arrived in April from Kharpert, it was determined that the wisest course of action was to burn the archives, which they did, taking two weeks to do so.

During the winter of 1914-15, Diyarbakir had a typhus outbreak. Dr. Smith offered his services to Hamid Bey, the governor of the Diyarbakir province. His offer was never accepted or even acknowledged; Smith suspected why but never divulged his suspicions. Hamid Bey had mostly a tolerant view toward the Armenians. However, possibly sensing his position was at risk, in February of 1915 he voiced his frustration with the brazenness of Armenian deserters who roamed the roofs of the city. He demanded they be turned in and many did so upon the urging of the Armenian bishop. However, this was not enough to save Hamid Bey, as he was replaced in March by Mehmed Reshid, a much more willing participant in the destruction of the Armenians.

Dr. Smith and his wife spent the first six months abroad in Paris learning French and making final preparations for missionary life. After initially stopping at the Bible House in Constantinople, where Dr. Smith passed an exam that allowed him to practice medicine, and attending a missionary conference in Jerusalem, they traveled to Aintab with Dr. Henry Atkinson, who was headed back to Kharpert from the conference.

The first six months in Aintab definitely required an adjustment for the Smiths. In October 1913, their first child, Arthur, was born. The birth was a difficult one for Bessie as she developed several post-partum hemorrhages. In addition, Dr. Smith felt certain that deficiencies existed in his training due to a truncated internship. In Aintab, he was learning from Dr. Fred Shepard, a 30-year veteran missionary. Yet, he felt the large staff already in place in Aintab limited his exposure to work crucial to his development. He offered that it might be beneficial to spend time in Talas while one of the physicians there was on leave to America, a view shared by Dr. Shepard. Dr. Smith had been destined for Diyarbakir from the beginning and, at the very least, felt a nurse would be a necessity there.

In early 1914, Dr. Smith had appendicitis that required emergency surgery. With his illness and Bessie’s long recovery from giving birth, the primary objective of learning Turkish was prolonged. Letters home tell of missionary life at the station and descriptions by proud parents of the growth of their son Arthur. They also warn their parents “not to print anything about the people here which we may send you, for there are Turkish correspondents in America who read the papers and everything about Turkey is sent right back here to the Sultan.”

After about a year in Aintab, the Smiths traveled to Kharpert, passing through Urfa and Diyarbakir where they were able to see their future quarters. They spent the summer of 1914 in Kharpert, where around 50 missionaries and their families attended the annual conference.

In early August, letters home contained the first mention of the anticipated war. Soon, the government began enlisting men between the ages of 20-45. Dr. Smith wrote, “This has caused great anxiety locally, especially among the Armenians. Also the Turks are not at all pleased.” Dr. Smith was able to buy a thoroughbred Arabian horse for 65-75 percent of the true value because the owner feared the horse would be requisitioned by the army.

Interestingly, around this time it seems that many of the Smiths’ letters home never arrived. This caused their families some anxiety and led to inquiries at the State Department.

Diyarbakir

They were unable to leave for Diyarbakir until the end of October 1914. Once in Diyarbakir, correspondence could no longer be done in English, as the government required either Turkish or French be used. Regardless, due to the conditions, there was little correspondence from the Smiths during their time in Diyarbakir.

After the official outbreak of the war, the British consul in Diyarbakir left the papers of the consulate with the Smiths. The intention was to transfer the archives to the American consulate in Kharpert when circumstances would allow. However, when nurse Margaret Campbell arrived in April from Kharpert, it was determined that the wisest course of action was to burn the archives, which they did, taking two weeks to do so.

During the winter of 1914-15, Diyarbakir had a typhus outbreak. Dr. Smith offered his services to Hamid Bey, the governor of the Diyarbakir province. His offer was never accepted or even acknowledged; Smith suspected why but never divulged his suspicions. Hamid Bey had mostly a tolerant view toward the Armenians. However, possibly sensing his position was at risk, in February of 1915 he voiced his frustration with the brazenness of Armenian deserters who roamed the roofs of the city. He demanded they be turned in and many did so upon the urging of the Armenian bishop. However, this was not enough to save Hamid Bey, as he was replaced in March by Mehmed Reshid, a much more willing participant in the destruction of the Armenians.

|

Reshid Bey immediately began the arrest and imprisonment of leading Armenians under the premise that they had sheltered the deserters. A group of eight Greek deserters had been found hidden in an Armenian school and they “turned state’s evidence with a vengeance.” The Greeks offered the names of notable Armenians as having supplied protection. However, the names given were actually of those who had opposed the Greeks hiding in the Christian quarter.

Thus began the all too familiar genocidal plan in Diyarbakir. Armenian homes were searched for weapons. “Men were imprisoned right and left and tortured to make them confess the presence and place of concealment of arms. Some went mad under torture. The Gregorian church on several occasions was ransacked from top to bottom and underneath–nothing found.” Dr. Smith procured some weapons so that Mrs. Smith would be left with some method of protection were he to travel to villages in the region. He had two revolvers and attempted to buy two more. However, because of the government search for weapons, the package arrived with just ammunition and a rifle. Dr. Smith attempted to get rid of these, but conditions did not allow for their disposal until two to three days later. |

As the prison filled to overflowing, typhus set in, but Dr. Smith’s attempts to visit the prison, in particular to see the representative of the Standard Oil Company, Stepan Matossian, were rejected. At the gate, a guard said, “Let him die like a dog.” Those imprisoned, around 600 Armenians and Syrians, were placed on rafts in June, ostensibly to be sent to Mosul, Iraq, but were killed on the way. The Armenian bishop was horribly tortured and killed.

Conditions deteriorated further. Muslims of the city would not acknowledge Christians on the street, while Muslim children would throw stones at Christians without fear of reprisal. Even Dr. Smith was subjected to stones thrown by children.

Dr. Smith wrote, “Diyarbakir is an interior province with extremely few foreigners—an ideal setup to find out how to solve the Troublesome Armenian problem: Massacre and Deportation, or both combined. Talaat, Enver, and Jemal were fiends from hell itself.”

In May, villagers began arriving in Diyarbakir with stories of “killing and plundering by the Kurds.” Karabash, about four miles east of Diyarbakir, had a mixed population of Armenians (~10 percent) and Assyrians (~90 percent). The village had already been searched for weapons and cleared of leading men when it was surrounded and attacked by Kurds around May 18. Some of the villagers escaped to a neighboring Muslim village. There they were protected until the Muslims ran out of ammunition. Gendarmes were sent to ensure no survivors reached Diyarbakir.

Only 20 of the almost 700 from Karabash reached Diyarbakir. Dr. Smith noted wounds caused by swords, knives, axes, and bullets. In particular, one woman had her “hand severed at the wrist” and perished. Two children and one woman had deep cuts along the base of the neck that indicated attempted decapitations. A boy from a different village had a three-week old bullet wound that entered the left side of the nose and exited on the right side of the neck. Finally, a boy of about nine years had a “severed piece of skull” caused by an axe or sword. He soon died as well.

Dr. Smith had been warned by a member of parliament to not treat these victims. “Have nothing to do with these poor villagers. They are the victims of the government.” But Dr. Smith felt it his duty and refused no one who needed his care.

Thomas Mugerditchian, British consular agent who fled Diyarbakir on the eve of these events, wrote based on survivor testimony: “Throughout all these tortures the eyes of all Armenians who were so shamefully treated were turned towards one, only one, human being who could possibly come to their assistance, the American missionary Dr. Smith. This self-sacrificing man took no notice whatever of hard work and labour but did all that was humanly possible to relieve, help, comfort and cheer the dying Armenians. Drugs and medicine to those who had been through tortures, wounds and bruises, bread and even fruits to the hungry, money to the needy, all these he freely and gladly offered to all who needed them. He ministered to their last needs, prayed with the dying, closed the eyes of the dead.”

The following week, with the refugees filling the mission property, the authorities kept the premises under constant surveillance and attempted at least one search, which Dr. Smith resisted on the grounds that it was an American property. Dr. Smith sent word to Kharpert requesting Henry Riggs come to Diyarbakir; he set out on May 29, arriving on June 1. Riggs heard stories of arrests and tortures in numerous towns along the way and was inundated with terrorized visitors upon arriving in Diyarbakir. Riggs “soon found that [Dr. Smith] was doing remarkable work at the time of the crisis.” Upon his return to Kharpert, Riggs described the dire situation in Diyarbakir to Leslie Davis, the American consul, as “the worst state of terror he had ever seen: not an Armenian man dared appear on the streets; soldiers were stationed on the roofs of the houses ready to shoot at sight any Armenian.” Riggs would reflect, “This was pitiful and heartbreaking for I realized, as they did not, how utterly helpless I was to do anything to ward off the disaster that the people dreaded.”

The authorities regarded Riggs’ arrival with suspicion and worried he was actually the consul, which “wouldn’t have been at all to the liking of the local government.” Dr. Smith had asked Riggs to come to Diyarbakir more for guidance than to help with the work. It was clear from the start that Dr. Smith would not leave his post. “Come what may, he felt that he must stand by the poor people who looked to him for help and protection.”

However, the incredible strain had taken a toll on Mrs. Smith. It would be best, they felt, if she and little Arthur joined the other missionaries in Kharpert. Leaving Diyarbakir had become no easy matter. The officials gave Riggs the run-around. In addition, the young Armenian boy who had been Riggs’ driver from Kharpert had been imprisoned under the pretense that he was a deserter. Riggs knew this to be false but was powerless to do anything about it.

Riggs, Mrs. Smith, and her son, Arthur, set out for Kharpert on June 3. Upon leaving the city, the party was searched. Dr. Smith protested on the basis that the United States and Turkey were on friendly terms. But Reshid would not see him; it was stated that the capitulations had been abolished, and the search proceeded. Among the papers and letters taken from Mrs. Smith was a cipher code meant as a way for her to communicate with her husband.

The code, devised for use by the missionaries, was a simple translation of the meaning of an innocent sentence into what was really meant. There were 24 sentences on each side. Some examples supplied by Dr. Smith of the innocent phrases are as follows:

#1 Have New York drafts been received

#2 Give Preston financial aid

#3 Books sent prepaid

#4 Do not send books; await letter, etc.

Some of the true meanings were as follows:

#1 Institutions closed by government

#2 Trying to leave; government refuses guard

#3 Massacre begun

#4 Massacre in villages

#5 Personal liberty violated

#6 Foreigners in extreme danger

#7 Conditions worse

#8 How are conditions?

#9 Embassy notified

#10 Prominent Armenians imprisoned

#11 Brutal tortures

#12 Women violated

#13 Property seized

Dr. Smith felt this would mean trouble, but Riggs thought it would be overlooked. They agreed that if no word was received from Dr. Smith in three days, then something had happened.

Riggs underestimated the importance of the cipher to the Turkish officials. While it was claimed as proof of seditious acts, it became quite clear that the real threat was it being used to communicate to the outside world that there were crimes currently being carried out against the Armenians.

On the journey to Kharpert, they came upon Armenian men from Chungush with hands bound and under guard. While Riggs recognized some of the men, only one acknowledged him by holding up four fingers. Riggs did not understand the meaning of this until they came upon the most recent four victims of this group. Riggs wrote:

A little further on I came to the place where the party had evidently stopped for lunch. There lay the bodies of two elderly Armenians. They had been stripped except for their shirts, and were laid in such a position as to expose their persons to the ridicule of passersby, and on the abdomen of each was cast a large stone. They had evidently been murdered there at the noon hour and then brutal guards had stopped to leave behind them the signs not only of violence but of mockery and insult.

Riggs and Mrs. Smith arrived in Kharpert on June 5 and found that conditions had deteriorated. Riggs now felt that the actions being taken were ordered from the central government. Consul Davis sent word to Ambassador Morganthau that Riggs had traveled to Diyarbakir. Two days later, the rooms of Mrs. Smith and Henry and Ernest Riggs were searched by the authorities, and a “good many papers” were taken and sent to Diyarbakir.

Meanwhile on June 5, police arrived at the mission property in Diyarbakir. Dr. Smith protested the search to no avail. All papers, books, three revolvers, and even Dr. Smith’s passport were confiscated. He was questioned about the cipher code that had been found on Mrs. Smith, although they did let him know that she had arrived safely in Kharpert. Two of the boys that worked at the mission were taken to prison. Two days later, Badveli Hagop Andonian was also imprisoned, as were two other servants of the mission. Thus, nurse Mariam Baghdasarian, her mother (who was the mission cook), and her younger brother were the only ones left at the mission with Dr. Smith.

Mariam was a graduate of Euphrates College. The strength of character and loyalty she showed to Dr. Smith left a debt of gratitude he carried throughout the remainder of his life.

One of the servants, Mugerdich, was tortured while in prison. Under such pressure, he indicated that Dr. Smith was Armenian and that he had been the agent of Harrison Maynard to incite insurrection in Diyarbakir, as had happened at Van. A group with Maynard had passed through Diyarbakir on their way to the U.S. on leave from May 21-23. They had come under suspicion as well.

The Badveli was also tortured into confessing fictitious plots against the government. He was later murdered, as was Mugerditch. Only Mariam and her brother Ohannes were to survive.

On June 16, Dr. Smith received word that he would be deported. He asked to travel through Kharpert to meet his wife and son. This was refused, and thus Mrs. Smith was sent for. He also asked that the Baghdasarians be allowed to leave with them, but this was refused. Dr. Smith had to leave everything behind, including deeds to property that the mission owned; his passport was also withheld.

For two weeks, Mrs. Smith received no word from Dr. Smith and feared he had been imprisoned. Finally, on June 17, word was received that he was being sent out of the country and that Mrs. Smith and Arthur should be sent to join him. No American was allowed to travel with her, but Davis was able to have his former kavass, Ahmed, accompany Mrs. Smith to Diyarbakir. They arrived in Diyarbakir on June 22.

They left Diyarbakir on June 23 and arrived in Ourfa 4 days later. American missionary and Vice-Consul Francis Leslie was allowed to be responsible for the Smiths while in Ourfa for six days. They were sent on to Aleppo, where Dr. Smith was placed in prison, “a dirty, dark, sultry hole with about 15 Armenians and Kurds, mostly the former.” These prisoners told the now familiar story of marches, imprisonment, and tortures. Consul Jesse Jackson soon secured Dr. Smith’s release.

Dr. Shepard was also in Aleppo at that time and together they visited Jemal Pasha. Jemal said to Dr. Smith, “You know, Doctor, when a patient has gangrene of the leg, the doctor doesn’t pay much attention to the little toe.” Dr. Smith interpreted the leg as being the Armenian problem, and he the little toe.

Dr. Shepard helped Dr. Smith acquire the necessary papers, as he still had no passport. The Smiths were then sent on to Beirut, where they arrived on July 16. Dr. Smith received an ordinary permit at this time and thought he would be able to leave. An attempt was made on July 20, but they were held up and Dr. Smith was thrown in prison once again.

On Aug. 3, he appeared before a courtmartial. At the trial, Dr. Smith was questioned in detail about the cipher, the meaning of each phrase, and how the cipher would work. He was also asked who developed the cipher and who had copies (e.g., other missionary stations, the Board in the U.S., etc). Dr. Smith was released and, within a few days, he and his family were able to board a ship headed to Greece.

The story of Dr. and Mrs. Smith does not end here. With the approval of the Missionary Board he volunteered to serve as a physician for the Red Cross for a time on the Caucasus front caring for wounded Russian and Turkish soldiers. Then they both were sent as missionaries to the Philippines. Bessie would die during the birth of her fifth child in the Southern Philippines at the end of 1924, but Floyd Smith spent the next 30+ years there continuing his medical mission and later working as an industrial doctor for the Insular lumber Company. During World War II, he fled to the mountains on the island of Negros with Filipinos but was captured and imprisoned by the Japanese for over 3 years in various internment camps including Negros, Bacolod, Los Banos and Santo Tomas. Throughout his imprisonment he provided medical care to other prisoners. Tellingly, at Santo Tomas during the last months of the war he personally attended to 50 of the 80 internees who died from starvation.

Quite a life as a medical missionary: early in his career swept up in and a witness to the Armenian Genocide including time in a Turkish prison during WWI, and then a decades-long medical career in the Philippines culminating in capture and internment by the Japanese during WWII.

Conditions deteriorated further. Muslims of the city would not acknowledge Christians on the street, while Muslim children would throw stones at Christians without fear of reprisal. Even Dr. Smith was subjected to stones thrown by children.

Dr. Smith wrote, “Diyarbakir is an interior province with extremely few foreigners—an ideal setup to find out how to solve the Troublesome Armenian problem: Massacre and Deportation, or both combined. Talaat, Enver, and Jemal were fiends from hell itself.”

In May, villagers began arriving in Diyarbakir with stories of “killing and plundering by the Kurds.” Karabash, about four miles east of Diyarbakir, had a mixed population of Armenians (~10 percent) and Assyrians (~90 percent). The village had already been searched for weapons and cleared of leading men when it was surrounded and attacked by Kurds around May 18. Some of the villagers escaped to a neighboring Muslim village. There they were protected until the Muslims ran out of ammunition. Gendarmes were sent to ensure no survivors reached Diyarbakir.

Only 20 of the almost 700 from Karabash reached Diyarbakir. Dr. Smith noted wounds caused by swords, knives, axes, and bullets. In particular, one woman had her “hand severed at the wrist” and perished. Two children and one woman had deep cuts along the base of the neck that indicated attempted decapitations. A boy from a different village had a three-week old bullet wound that entered the left side of the nose and exited on the right side of the neck. Finally, a boy of about nine years had a “severed piece of skull” caused by an axe or sword. He soon died as well.

Dr. Smith had been warned by a member of parliament to not treat these victims. “Have nothing to do with these poor villagers. They are the victims of the government.” But Dr. Smith felt it his duty and refused no one who needed his care.

Thomas Mugerditchian, British consular agent who fled Diyarbakir on the eve of these events, wrote based on survivor testimony: “Throughout all these tortures the eyes of all Armenians who were so shamefully treated were turned towards one, only one, human being who could possibly come to their assistance, the American missionary Dr. Smith. This self-sacrificing man took no notice whatever of hard work and labour but did all that was humanly possible to relieve, help, comfort and cheer the dying Armenians. Drugs and medicine to those who had been through tortures, wounds and bruises, bread and even fruits to the hungry, money to the needy, all these he freely and gladly offered to all who needed them. He ministered to their last needs, prayed with the dying, closed the eyes of the dead.”

The following week, with the refugees filling the mission property, the authorities kept the premises under constant surveillance and attempted at least one search, which Dr. Smith resisted on the grounds that it was an American property. Dr. Smith sent word to Kharpert requesting Henry Riggs come to Diyarbakir; he set out on May 29, arriving on June 1. Riggs heard stories of arrests and tortures in numerous towns along the way and was inundated with terrorized visitors upon arriving in Diyarbakir. Riggs “soon found that [Dr. Smith] was doing remarkable work at the time of the crisis.” Upon his return to Kharpert, Riggs described the dire situation in Diyarbakir to Leslie Davis, the American consul, as “the worst state of terror he had ever seen: not an Armenian man dared appear on the streets; soldiers were stationed on the roofs of the houses ready to shoot at sight any Armenian.” Riggs would reflect, “This was pitiful and heartbreaking for I realized, as they did not, how utterly helpless I was to do anything to ward off the disaster that the people dreaded.”

The authorities regarded Riggs’ arrival with suspicion and worried he was actually the consul, which “wouldn’t have been at all to the liking of the local government.” Dr. Smith had asked Riggs to come to Diyarbakir more for guidance than to help with the work. It was clear from the start that Dr. Smith would not leave his post. “Come what may, he felt that he must stand by the poor people who looked to him for help and protection.”

However, the incredible strain had taken a toll on Mrs. Smith. It would be best, they felt, if she and little Arthur joined the other missionaries in Kharpert. Leaving Diyarbakir had become no easy matter. The officials gave Riggs the run-around. In addition, the young Armenian boy who had been Riggs’ driver from Kharpert had been imprisoned under the pretense that he was a deserter. Riggs knew this to be false but was powerless to do anything about it.

Riggs, Mrs. Smith, and her son, Arthur, set out for Kharpert on June 3. Upon leaving the city, the party was searched. Dr. Smith protested on the basis that the United States and Turkey were on friendly terms. But Reshid would not see him; it was stated that the capitulations had been abolished, and the search proceeded. Among the papers and letters taken from Mrs. Smith was a cipher code meant as a way for her to communicate with her husband.

The code, devised for use by the missionaries, was a simple translation of the meaning of an innocent sentence into what was really meant. There were 24 sentences on each side. Some examples supplied by Dr. Smith of the innocent phrases are as follows:

#1 Have New York drafts been received

#2 Give Preston financial aid

#3 Books sent prepaid

#4 Do not send books; await letter, etc.

Some of the true meanings were as follows:

#1 Institutions closed by government

#2 Trying to leave; government refuses guard

#3 Massacre begun

#4 Massacre in villages

#5 Personal liberty violated

#6 Foreigners in extreme danger

#7 Conditions worse

#8 How are conditions?

#9 Embassy notified

#10 Prominent Armenians imprisoned

#11 Brutal tortures

#12 Women violated

#13 Property seized

Dr. Smith felt this would mean trouble, but Riggs thought it would be overlooked. They agreed that if no word was received from Dr. Smith in three days, then something had happened.

Riggs underestimated the importance of the cipher to the Turkish officials. While it was claimed as proof of seditious acts, it became quite clear that the real threat was it being used to communicate to the outside world that there were crimes currently being carried out against the Armenians.

On the journey to Kharpert, they came upon Armenian men from Chungush with hands bound and under guard. While Riggs recognized some of the men, only one acknowledged him by holding up four fingers. Riggs did not understand the meaning of this until they came upon the most recent four victims of this group. Riggs wrote:

A little further on I came to the place where the party had evidently stopped for lunch. There lay the bodies of two elderly Armenians. They had been stripped except for their shirts, and were laid in such a position as to expose their persons to the ridicule of passersby, and on the abdomen of each was cast a large stone. They had evidently been murdered there at the noon hour and then brutal guards had stopped to leave behind them the signs not only of violence but of mockery and insult.

Riggs and Mrs. Smith arrived in Kharpert on June 5 and found that conditions had deteriorated. Riggs now felt that the actions being taken were ordered from the central government. Consul Davis sent word to Ambassador Morganthau that Riggs had traveled to Diyarbakir. Two days later, the rooms of Mrs. Smith and Henry and Ernest Riggs were searched by the authorities, and a “good many papers” were taken and sent to Diyarbakir.

Meanwhile on June 5, police arrived at the mission property in Diyarbakir. Dr. Smith protested the search to no avail. All papers, books, three revolvers, and even Dr. Smith’s passport were confiscated. He was questioned about the cipher code that had been found on Mrs. Smith, although they did let him know that she had arrived safely in Kharpert. Two of the boys that worked at the mission were taken to prison. Two days later, Badveli Hagop Andonian was also imprisoned, as were two other servants of the mission. Thus, nurse Mariam Baghdasarian, her mother (who was the mission cook), and her younger brother were the only ones left at the mission with Dr. Smith.

Mariam was a graduate of Euphrates College. The strength of character and loyalty she showed to Dr. Smith left a debt of gratitude he carried throughout the remainder of his life.

One of the servants, Mugerdich, was tortured while in prison. Under such pressure, he indicated that Dr. Smith was Armenian and that he had been the agent of Harrison Maynard to incite insurrection in Diyarbakir, as had happened at Van. A group with Maynard had passed through Diyarbakir on their way to the U.S. on leave from May 21-23. They had come under suspicion as well.

The Badveli was also tortured into confessing fictitious plots against the government. He was later murdered, as was Mugerditch. Only Mariam and her brother Ohannes were to survive.

On June 16, Dr. Smith received word that he would be deported. He asked to travel through Kharpert to meet his wife and son. This was refused, and thus Mrs. Smith was sent for. He also asked that the Baghdasarians be allowed to leave with them, but this was refused. Dr. Smith had to leave everything behind, including deeds to property that the mission owned; his passport was also withheld.

For two weeks, Mrs. Smith received no word from Dr. Smith and feared he had been imprisoned. Finally, on June 17, word was received that he was being sent out of the country and that Mrs. Smith and Arthur should be sent to join him. No American was allowed to travel with her, but Davis was able to have his former kavass, Ahmed, accompany Mrs. Smith to Diyarbakir. They arrived in Diyarbakir on June 22.

They left Diyarbakir on June 23 and arrived in Ourfa 4 days later. American missionary and Vice-Consul Francis Leslie was allowed to be responsible for the Smiths while in Ourfa for six days. They were sent on to Aleppo, where Dr. Smith was placed in prison, “a dirty, dark, sultry hole with about 15 Armenians and Kurds, mostly the former.” These prisoners told the now familiar story of marches, imprisonment, and tortures. Consul Jesse Jackson soon secured Dr. Smith’s release.

Dr. Shepard was also in Aleppo at that time and together they visited Jemal Pasha. Jemal said to Dr. Smith, “You know, Doctor, when a patient has gangrene of the leg, the doctor doesn’t pay much attention to the little toe.” Dr. Smith interpreted the leg as being the Armenian problem, and he the little toe.

Dr. Shepard helped Dr. Smith acquire the necessary papers, as he still had no passport. The Smiths were then sent on to Beirut, where they arrived on July 16. Dr. Smith received an ordinary permit at this time and thought he would be able to leave. An attempt was made on July 20, but they were held up and Dr. Smith was thrown in prison once again.

On Aug. 3, he appeared before a courtmartial. At the trial, Dr. Smith was questioned in detail about the cipher, the meaning of each phrase, and how the cipher would work. He was also asked who developed the cipher and who had copies (e.g., other missionary stations, the Board in the U.S., etc). Dr. Smith was released and, within a few days, he and his family were able to board a ship headed to Greece.

The story of Dr. and Mrs. Smith does not end here. With the approval of the Missionary Board he volunteered to serve as a physician for the Red Cross for a time on the Caucasus front caring for wounded Russian and Turkish soldiers. Then they both were sent as missionaries to the Philippines. Bessie would die during the birth of her fifth child in the Southern Philippines at the end of 1924, but Floyd Smith spent the next 30+ years there continuing his medical mission and later working as an industrial doctor for the Insular lumber Company. During World War II, he fled to the mountains on the island of Negros with Filipinos but was captured and imprisoned by the Japanese for over 3 years in various internment camps including Negros, Bacolod, Los Banos and Santo Tomas. Throughout his imprisonment he provided medical care to other prisoners. Tellingly, at Santo Tomas during the last months of the war he personally attended to 50 of the 80 internees who died from starvation.

Quite a life as a medical missionary: early in his career swept up in and a witness to the Armenian Genocide including time in a Turkish prison during WWI, and then a decades-long medical career in the Philippines culminating in capture and internment by the Japanese during WWII.